Propositions as types and the future of programming

What’s all the fuss about?

Quite recently, Philip Wadler published the paper “Propositions as Types”

If I understood this correctly, this is about the fact that the application of a function to a type is also a type. Based on this observation, we could describe a whole app in types.

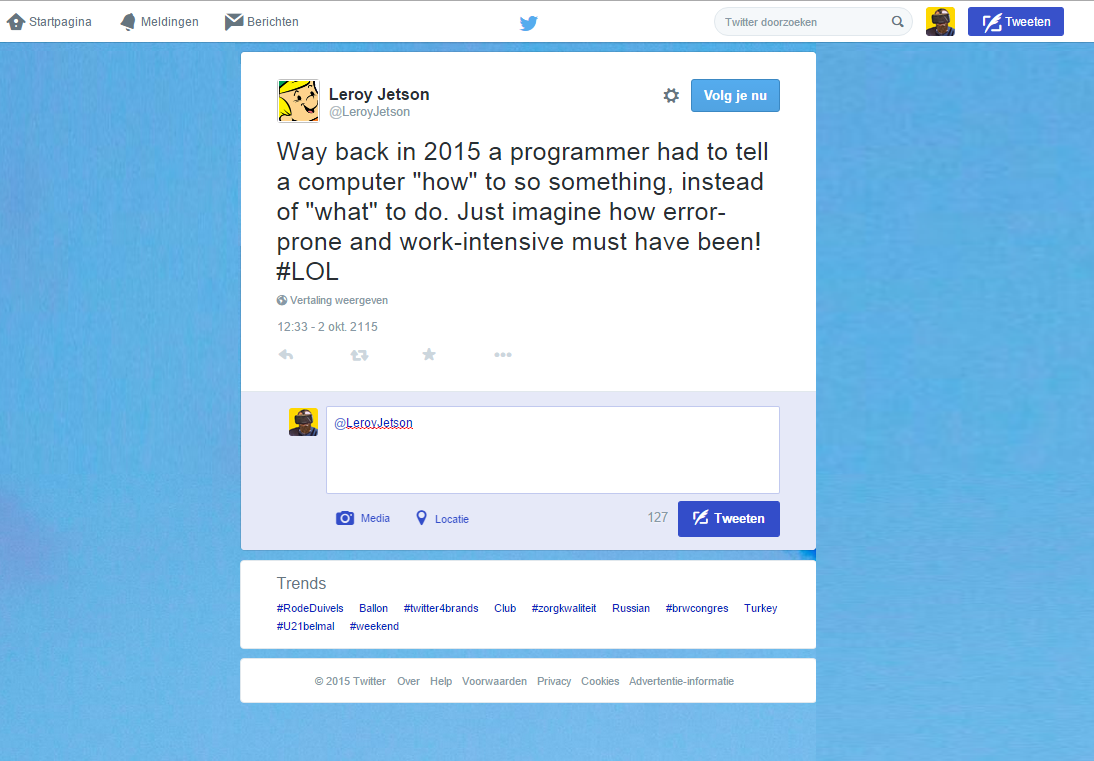

As we can easily compose types using product and sums, this would imply that you would no longer have to write an application by telling your computer how to do things, you would just tell your computer

what you would want it to do, and it will deduct the code/proof itself. ( It might require some assistance from you, but the theorem prover will, by proving the theory, actually write the program.)

Why do you think this is the future?

Some time ago I created a small study group to learn some Idris, a dependently typed language. While I think it is way to early to be usable right now, I do believe I have seen a glimpse of the future.

But Why? - bis

Let’s say we have a simple program that needs to subtract 2 from a natural number.

In some future programming language you would define this as follows:

data Nat = Zero | Succ Nat

So a natural number is defined as the successor of it's predecessor.

This means that we can represent any natural number using types, f.e.:

0 = 0

1 = Succ 0

2 = Succ 1

2 = Succ (Succ 0)

Let’s say we have a functiontype called Sub2 that decrements a natural number by 2.

(I know the example is really stupid, but it’s as far as I can go in a single blog post.)

data Sub2 = (Succ ( Succ (Nat))) a => Sub2 a

If we now try to compile

data App = Sub2 0

this would give a compilation error, as the type of Sub2 expects a type of Succ (Succ (Nat)),

which is why you will not be able to define these statements; they will not typecheck.

This would compile:

data App = Sub2 3

As the compiler would be able to deduce that:

Data App = Sub2 3

Data App = Sub2 (Succ(Succ 1))

Data App = 1

Of course, adding numbers by incrementing them one by one (using typechecks) would be really slow, so the compiler would figure out how to properly implement this, but those are just implementation details.

As you can see, due to the dependent types, your compiler could even figure out that the whole Sub2 operation

is redundant, and that it can just return a 1 - or a Succ 0 if you prefer this -.

What will all of this lead to?

On the first computers, people had to program using hardware switches. We gradually evolved to the current type of programming using increasingly higher level of abstractions, which are tied less and less to the internals of a computer.

If I understood it correctly, Philip’s paper describes what might lead to the next level of abstraction: no longer telling the computer how to do something, but just specifying what we need.